Head Lines are lines drawn by political leaders. Signatures of the powerful figures who shape our world. They are the subject matter of the paintings, which use an entirely unique approach to make politics speak. Paintings that are linked by their formal nature, an intense use of colour, a a tight linear structure and the eventful story that they tell. They are also connected by their content. However abstract the paintings may seem, their intrinsic meaning is actually extremely concrete and rooted in reality. Textual elements reveal themselves. Handwriting. As unique as only signatures can be. These elements open our eyes to the story being told by these paintings.

They show details and individual shapes of particular signatures. These are signatures that impact our present-day lives. Behind them are leaders who shape our generation’s world, our lives, as well as our headlines – from Trump to Merkel, from Viktor Orbán to Xi Jinping. World-famous personalities who we think we know well. However, we have never seen them in this light before. While their faces are all too familiar, these paintings provide an insight into their actions, their decision-making processes, their ways of shaping the future and what they endorse. They depict motions which lead to important changes being put into motion. The paintings do not disclose the full signatures. It’s not the facts that matter but the momentum. The characteristics and inherent features of the motions. The living nature of the moment. The personal and individual. Minds produce lines. Head Lines. The leaders at the very top and the decisions that are made there.

Behind the level of the subject, described by the title Head Lines, we see another level of creative imagination. The linear structures create visual spaces. They give depth to the area they occupy – as well as the area they do not occupy. They often leave large parts of the painting’s surface untouched, thus bringing these spaces into the spotlight. They give form to the “unwritten” space. This results in paintings which tell very distinct stories. It is not just the background colour nor the person’s handwriting which create individuality, but also the imaginary spaces with their wealth of associations. The movements of the lines have an impact not just in themselves, through their flow and their drama, but also through the space outside the lines, which they help shape.

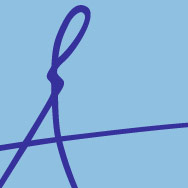

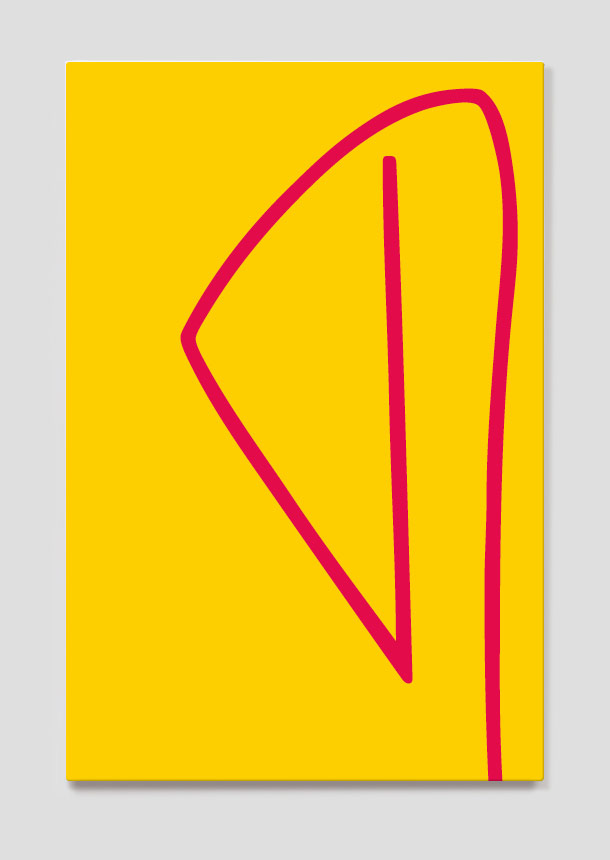

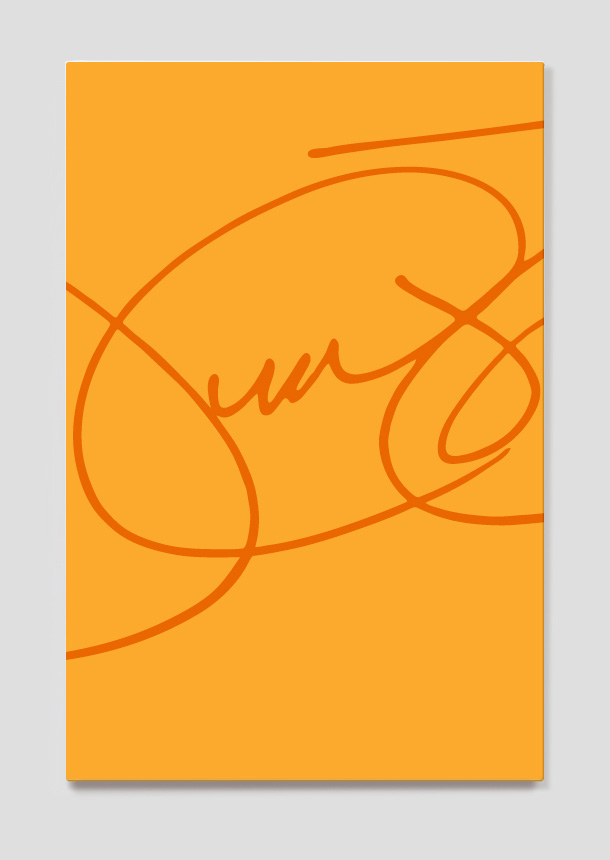

Head Lines # 1-21.7

2015

Shinzo Abe

Prime Minister

acrylic and silk screen

on canvas

47,24 x 31,5 x 1,77 in

(120 x 80 x 4,5 cm)

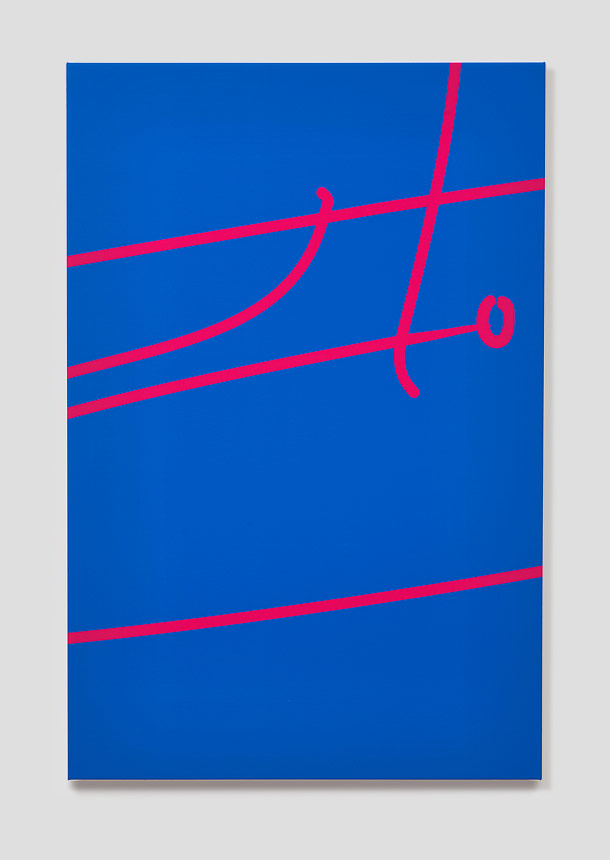

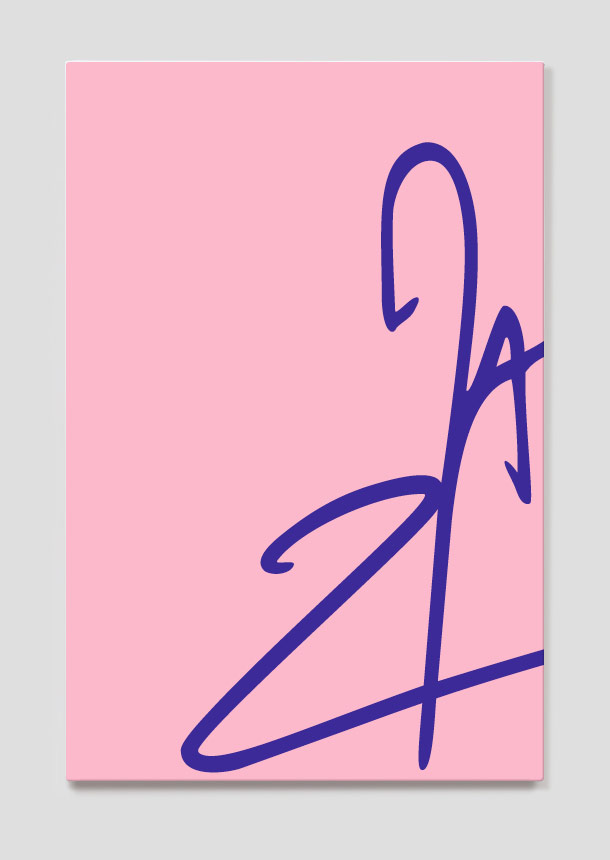

Head Lines # 2-04.8

2015

Barack Obama

US President

acrylic and silk screen

on canvas

47,24 x 31,5 x 1,77 in

(120 x 80 x 4,5 cm)

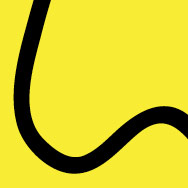

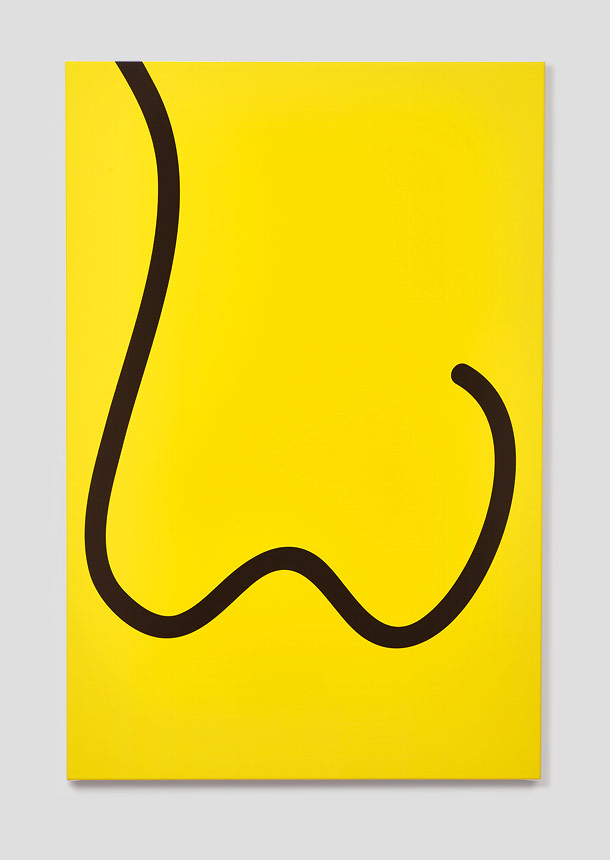

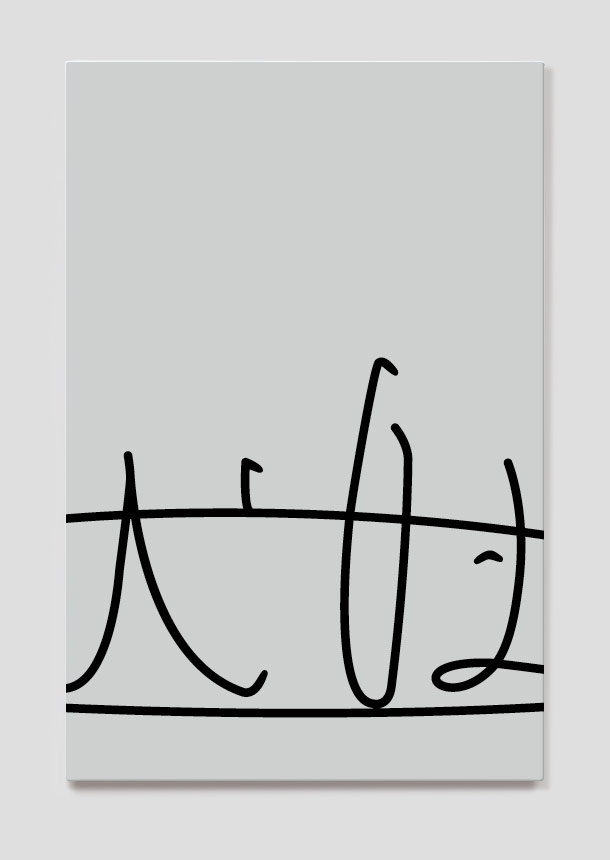

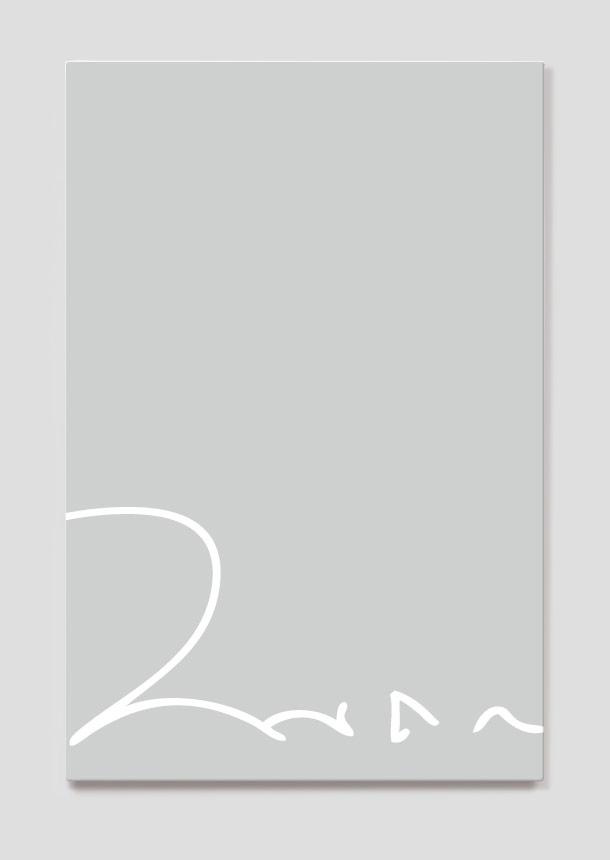

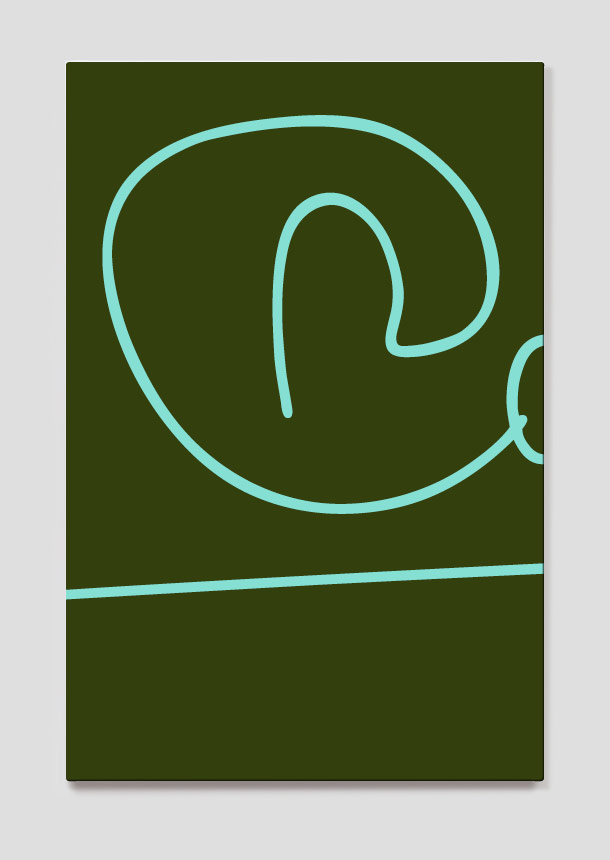

Head Lines # 3-17.7

2015

Angela Merkel

Federal Chancellor

acrylic and silk screen

on canvas

47,24 x 31,5 x 1,77 in

(120 x 80 x 4,5 cm)

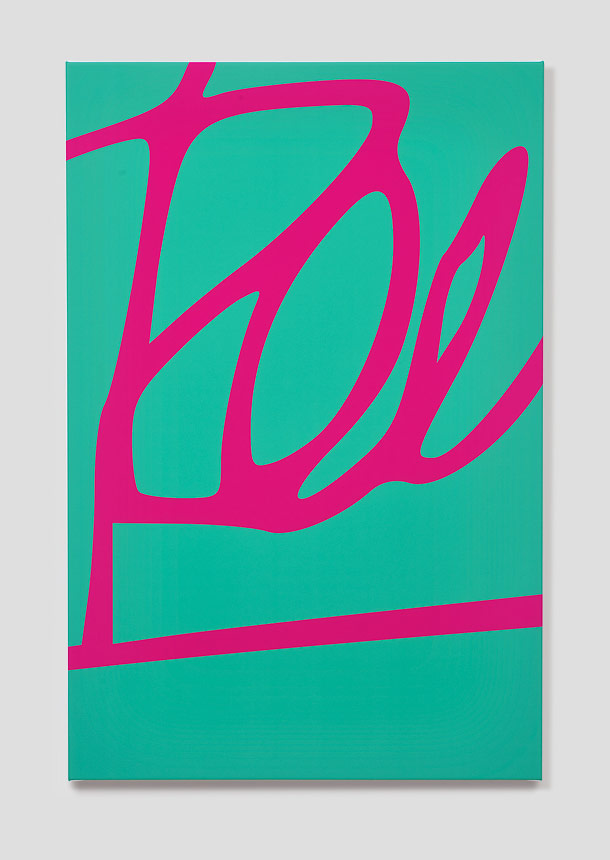

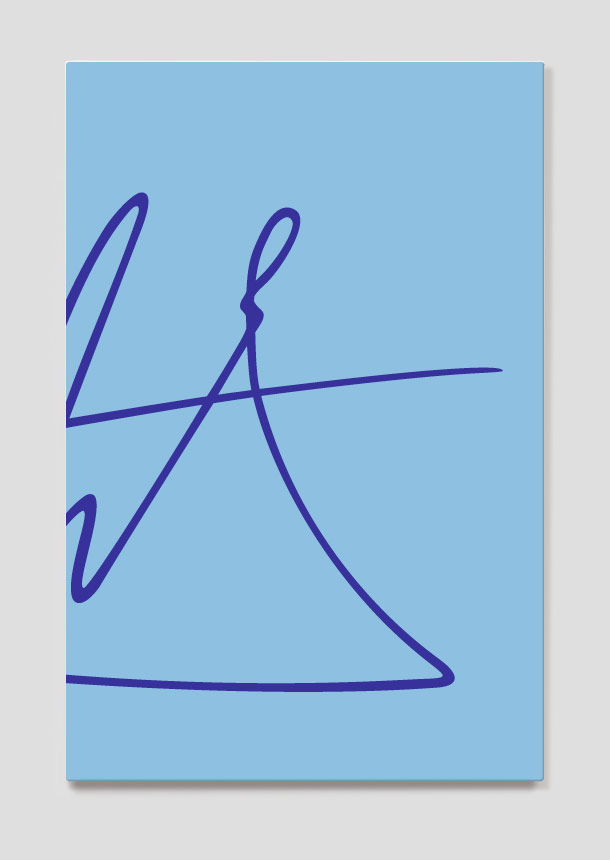

Head Lines # 4-12.8

2015

François Hollande

President

acrylic and silk screen

on canvas

47,24 x 31,5 x 1,77 in

(120 x 80 x 4,5 cm)

Head Lines # 5-30.4

2015

Stephen Harper

Prime Minister

acrylic and silk screen

on canvas

47,24 x 31,5 x 1,77 in

(120 x 80 x 4,5 cm)

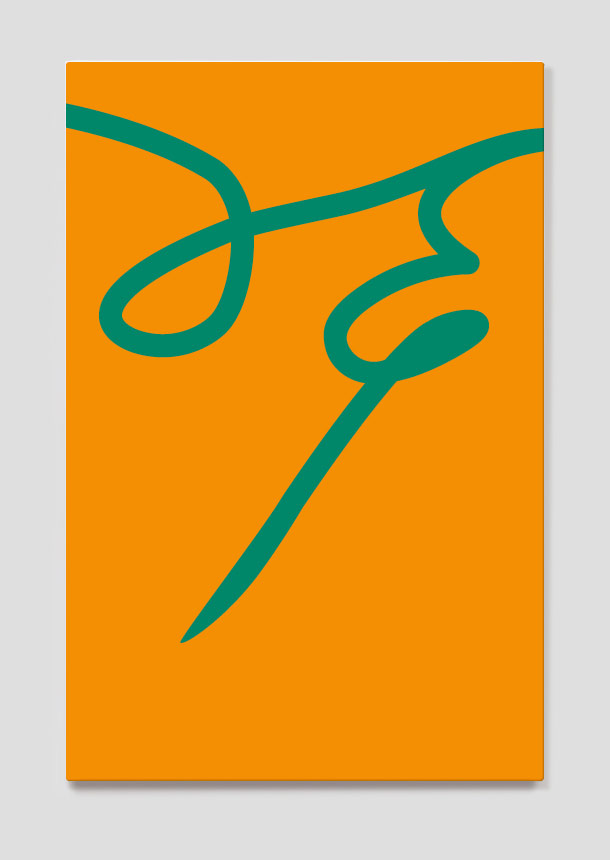

Head Lines # 6-11.1

2015

Matteo Renzi

Prime Minister

acrylic and silk screen

on canvas

47,24 x 31,5 x 1,77 in

(120 x 80 x 4,5 cm)

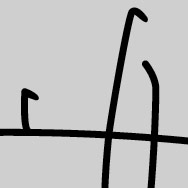

Head Lines # 7-09.10

2015

David Cameron

Prime Minister

acrylic and silk screen

on canvas

47,24 x 31,5 x 1,77 in

(120 x 80 x 4,5 cm)

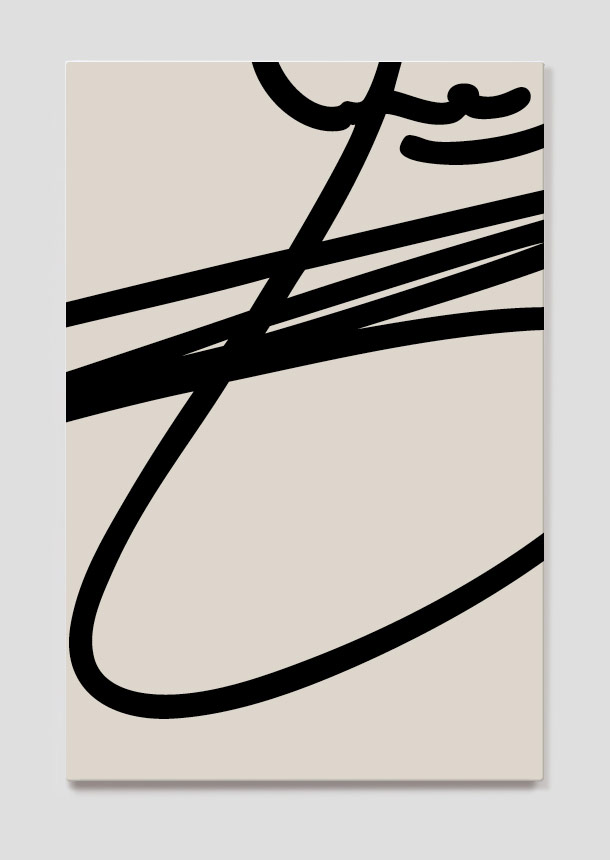

Head Lines # 8-07.10

2015

Vladimir Putin

President

acrylic and silk screen

on canvas

47,24 x 31,5 x 1,77 in

(120 x 80 x 4,5 cm)

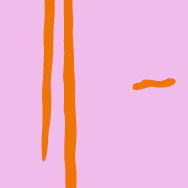

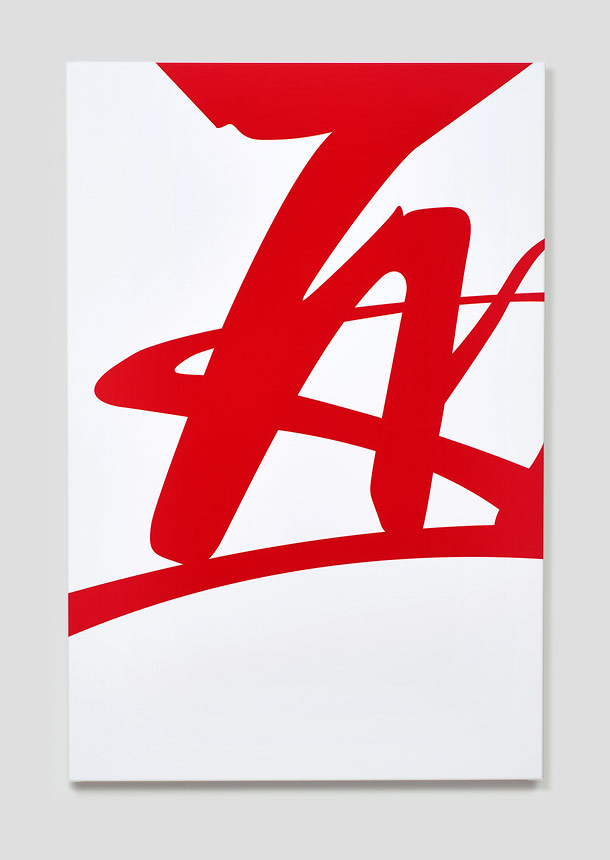

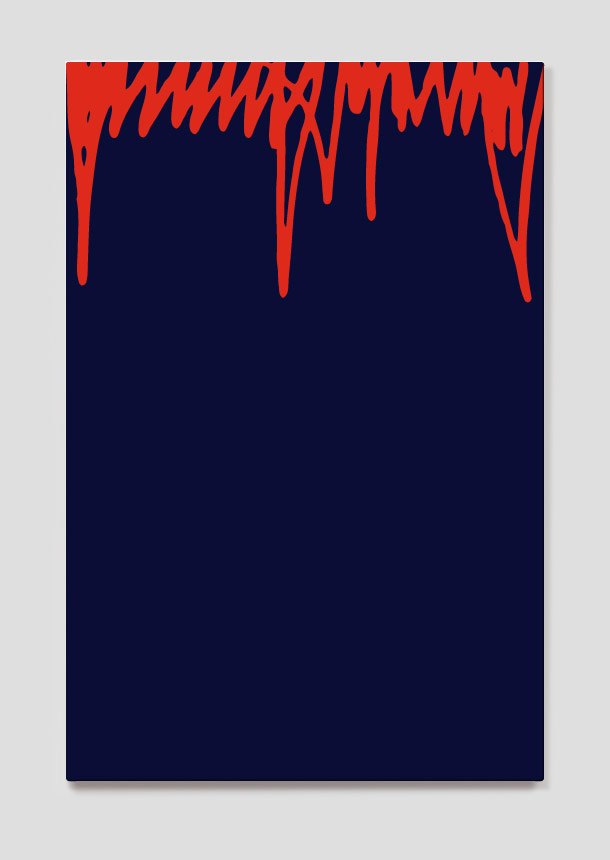

Head Lines # 10-14.6

2017

Donald Trump

President of the United States

ink on canvas

47,24 x 31,5 x 1,77 in

(120 x 80 x 4,5 cm)

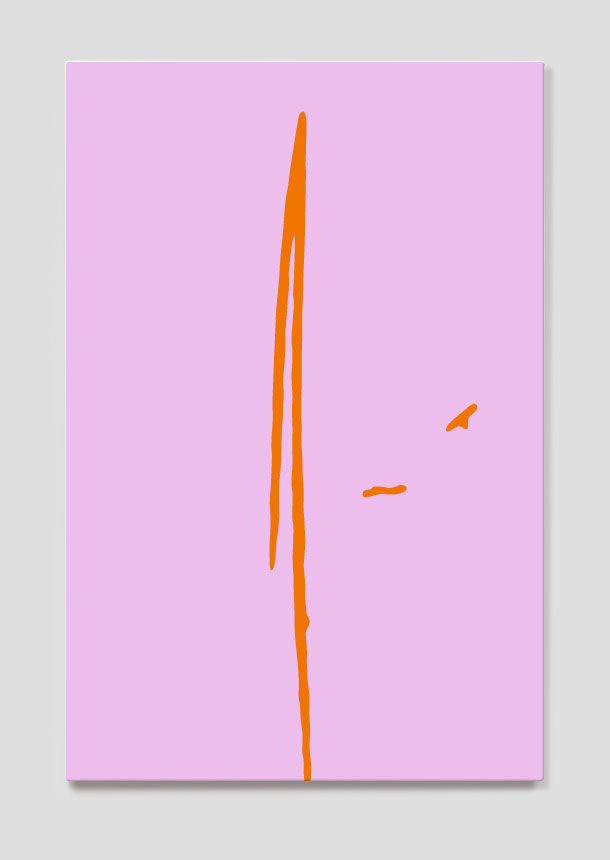

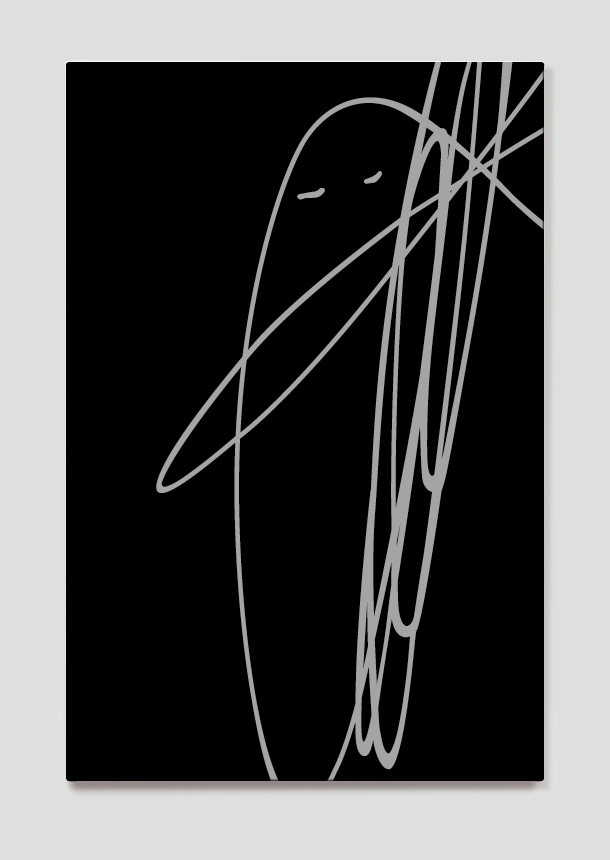

Head Lines # 9-08.1

2017

Kim Jong-un

Supreme Leader of North Korea

ink on canvas

47,24 x 31,5 x 1,77 in

(120 x 80 x 4,5 cm)

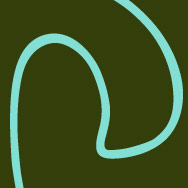

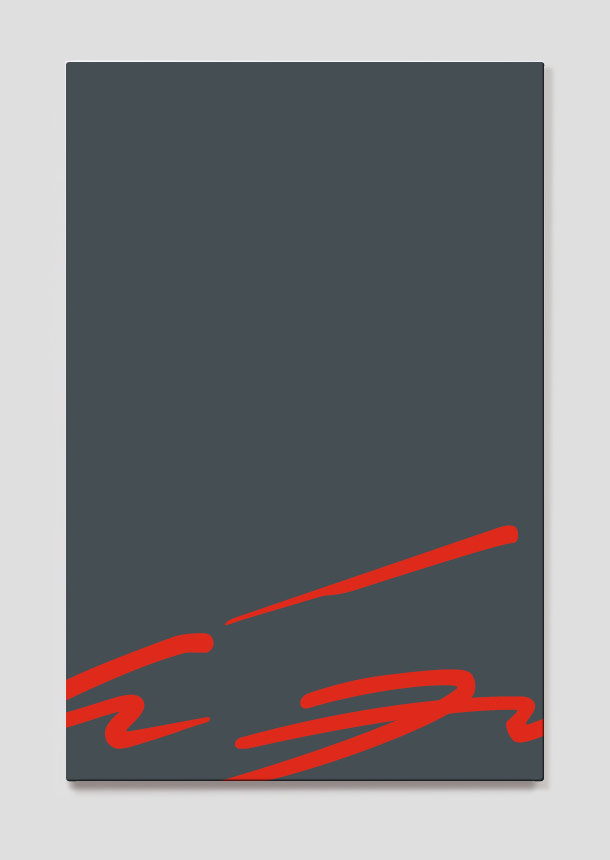

Head Lines # 11-31.5

2017

Viktor Orban

Prime Minister of Hungary

ink on canvas

47,24 x 31,5 x 1,77 in

(120 x 80 x 4,5 cm)

Head Lines # 13-27.8

2018

Sebastian Kurz

Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Austria

ink on canvas

47,24 x 31,5 x 1,77 in

(120 x 80 x 4,5 cm)

Head Lines # 14-27.3

2018

Mariano Rajoy

Prime Minister of Spain

ink on canvas

47,24 x 31,5 x 1,77 in

(120 x 80 x 4,5 cm)

Head Lines # 15-26.2

2018

Recep Tayyip Erdogan

President of Turkey

ink on canvas

47,24 x 31,5 x 1,77 in

(120 x 80 x 4,5 cm)

Head Lines # 16-21.12

2018

Emmanuel Macron

President of France

ink on canvas

47,24 x 31,5 x 1,77 in

(120 x 80 x 4,5 cm)

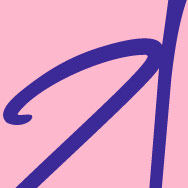

Head Lines # 17-01.10

2018

Theresa May

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

ink on canvas

47,24 x 31,5 x 1,77 in

(120 x 80 x 4,5 cm)

Head Lines # 18-28.7

2017

Alexis Tsipras

Prime Minister of Greece

ink on canvas

47,24 x 31,5 x 1,77 in

(120 x 80 x 4,5 cm)

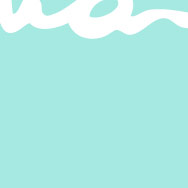

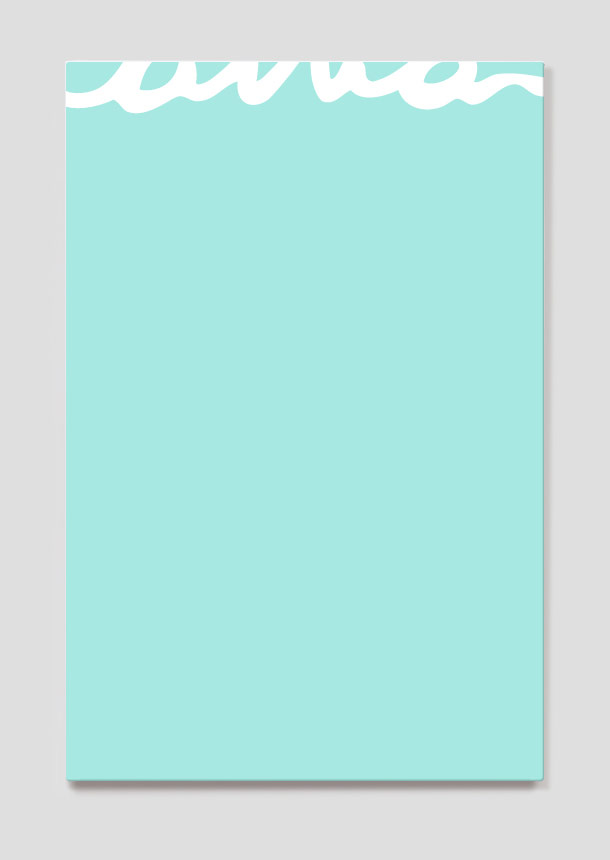

Head Lines # 19-25.12

2017

Justin Trudeau

Prime Minister of Canada

ink on canvas

47,24 x 31,5 x 1,77 in

(120 x 80 x 4,5 cm)

Head Lines # 20-20.7

2018

Enrique Pena Nieto

President of Mexico

ink on canvas

47,24 x 31,5 x 1,77 in

(120 x 80 x 4,5 cm)

Head Lines # 21-03.6

2017

Raul Castro

President of the Council of State of Cuba

ink on canvas

47,24 x 31,5 x 1,77 in

(120 x 80 x 4,5 cm)

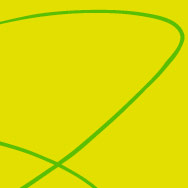

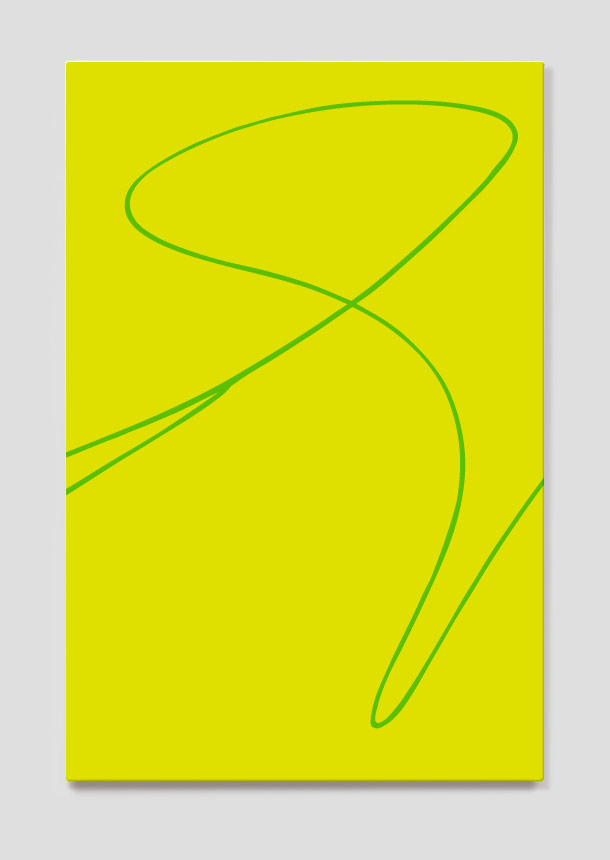

Head Lines # 12-28.7

2017

Hugo Chavez

President of Venezuela

ink on canvas

47,24 x 31,5 x 1,77 in

(120 x 80 x 4,5 cm)

Head Lines # 22-01.3

2017

Dalia Grybauskaite

President of Lithuania

ink on canvas

47,24 x 31,5 x 1,77 in

(120 x 80 x 4,5 cm)

Head Lines # 23-15.6

2017

Xi Jinping

President of the People’s Republic of China

ink on canvas

47,24 x 31,5 x 1,77 in

(120 x 80 x 4,5 cm)

Head Lines # 24-17.9

2018

Narendra Modi

Prime Minister of India

ink on canvas

47,24 x 31,5 x 1,77 in

(120 x 80 x 4,5 cm)

Head Lines # 25-12.11

2018

Hassan Rouhani

President of Iran

ink on canvas

47,24 x 31,5 x 1,77 in

(120 x 80 x 4,5 cm)

Head Lines # 26-11.9

2018

Bashar al-Assad

President of Syria

ink on canvas

47,24 x 31,5 x 1,77 in

(120 x 80 x 4,5 cm)

Head Lines # 27-26.9

2017

Petro Poroshenko

President of Ukraine

ink on canvas

47,24 x 31,5 x 1,77 in

(120 x 80 x 4,5 cm)

The symbols of power and the power of symbols

Politics and art each serve to give things shape, have each helped forge the history of humankind, and are connected with one another as much as they differ from one another. Both unfold as human expressions of life and creative ambitions; both relate to society and explore it in terms of its current state and its possibilities and future prospects. But each follows an entirely different logic. The medium of politics is power, the medium of art is form. While this alone is not an adequate description, it is obvious that political processes cannot be measured against aesthetic standards, which for an artwork are always fundamental.

The assertion that all art is political is just as arbitrary as the opposing claim of “l’art pour l’art”, art for art’s sake. There are doubtless artworks which are politically motivated in the literal sense of the word, and artistic positions which determinedly convey political content. These can be found in particular in literature and theatre, as well as in music and of course, last but not least, in the visual arts. Examples populate museums, government buildings, ministries and increasingly parliaments around the world. And many of these examples epitomise the dangers of instrumentalising art for political purposes, in the form of blatant propaganda, subtle persiflage, ideological glorification, targeted discrimination or demonstrative humiliation.

The cycle of paintings Head Lines by Joseph Carlson undoubtedly belongs to the category of political art and is clearly distinct from the aberrations mentioned above. Joseph Carlson illustrates neither concrete events nor abstract ideas. Like many artists, he deals with figures who are or were politically significant, but not in the familiar form of portraits displaying a likeness – accurate or otherwise – of the ruler in question. Instead, he uses symbols which are in equal measures stylised and authentic: signatures. He takes as his subject matter the signatures of the powerful, of the decision makers, who use their will to lay down acts of state and promote or prevent societal change.

Art is about perceptions, politics is about decisions. The signatures of the powerful are not necessarily powerful symbols; their influence does not arise from the symbols themselves, but rather from the acceptance of these symbols as valid, certified acts of will. Political decisions are expressed in both collective and individual votes; in laws, commands and orders. Their claim to validity has generally manifested itself, from antiquity to the modern digital age, in a visible piece of evidence: the signature.

It is here, in the dimension of the visible, that Joseph Carlson begins. He relies solely on the visual, on constant visibility independent of any occasion, of context or consequence. The Head Lines are not what they seem. They appear at first glance to be a contemporary form of calligraphy, and yet calligraphy, handwriting as an art form, is exactly what they are not.

The impact of a written symbol is entirely unaffected by its (aesthetic) form, while the aesthetic value of handwriting as art is not in the slightest determined by its (political) impact. Joseph Carlson’s Head Lines have a potent calligraphic element, abstaining from any even implicit depiction of occasion, outcome or effect. They show only what can be seen in these signatures: the handwriting, the flow, the rhythm. By emphasising a detail chosen at random, not for political but for aesthetic reasons, Carlson reduces the signature to the mere symbol. In this way, the image becomes more innocent than the subject. The Head Lines are neither signatures nor titles, but seemingly harmless symbols of powerful figures.

As we view the paintings, our imagination knows no bounds. If we were unaware of the subject of the work, we would form entirely different associations than we do in the knowledge of the person in question and the perception of their signature as a powerful version of many thousands of other written symbols. We know what happens through signatures, what can be ordered or brought about, prohibited or allowed, what actions are taken or left undone or deferred, what can be created or destroyed. Signatures reflect the power of individuals. Is this why they are usually illegible? Can the individual hide behind their own signature? Is it just by chance that handwritten signatures exude mystery, magic, genius, chaos?

Which signature belongs to whom? Which symbol is connected to which figure? It is a sobering realisation that we are unable to discern whether a signature is the work of an autocrat, a democrat or a despot. Joseph Carlson’s Head Lines are artworks, not documents. They could be seen as purely aesthetic projections and in fact, with certain rulers in mind, can perhaps only be borne in this way. We scrutinise the symbols for characteristics that might reveal the nature of the signatories, but we find none. The beholder is both fascinated and alarmed at once, almost like Belshazzar, king of Babylon, in the famous Rembrandt painting or in Heinrich Heine’s ballad: “Behold! Behold! upon the wall / A thing – a hand – came in the hall … / Magicians came, yet none at all / Could decipher the flame-script on the wall.”

The image is not the message: the message comes into being only in the mind of the beholder who is able to recognise the symbols of power and interpret the power of symbols.

Norbert Lammert

Symbols of will

What is a signature? Something unmistakable which every individual possesses, just like their body and perhaps also their soul. Nothing is more universal than a signature – and yet there is nothing more unique, nothing which sets us apart from one another more. Like our style, our signature serves the sole purpose of preventing us from being mistaken for anyone else. I sign, therefore I am: I am the one who signs my name. The painter, graphic artist and photographer Joseph Carlson illustrates this like no other in his series Head Lines, by illustrating the signature of our world. In around twenty works, Joseph Carlson thus convenes the signatories of our world and does what we can only dream of: he gathers contemporary heads of state for a vast collective project.

A remarkable idea which couples a utopian euphoria with the knowledge that it is doomed to fail. From Trump to Merkel and Macron to Xi Jinping, from Shinzō Abe to Putin and Matteo Renzi to Theresa May, the world hastens to demonstrate their presence and at the same time their power. Each of them signs the great book of the powerful, each one hopes to achieve something different with their signature: to give an order, to make common cause, to seal a pledge.

Let us look at them, these signatures by Joseph Carlson against intensely coloured backgrounds – the orange of Justin Trudeau, the yellow of Hugo Chávez, the red of Erdoğan: a character emerges, a temperament becomes visible. Everywhere they appear, these symbols illustrate the will of a woman, of a man. They are symbols of will: let us look at how these signatures have been magnified, taking up the whole page, fervently overflowing the space that is available to them, and that is not enough for them – the official bottom line of a letter or an agreement that here has taken on the dimensions of the work. These signatures press forward, spread out – they could almost be said to sit in state, so far as the space on the page allows it. They are like flags. The manifestation of the countries that are embodied in them. Hence the colours, hence their disproportionate significance.

And yet Joseph Carlson takes away their centre, he displaces them. Among these signatures, we will not find a single one that can be seen in its entirety, as is the case for us when we sign a document. Of Trump’s signature, only the lower part is visible – the top is cut off; of Alexis Tsipras’ signature, we see only the end – the beginning is missing. The signature of Kim Jong-un seems to be materialising from somewhere, while Hassan Rouhani’s is cropped on all sides. The name is always “too much”, it must be played with. Because the names of the greats of this world are more than just a surname, they are an image, and the fate of images today is to transcend – just consider how far they spread on the internet, how large they appear on the screens of our home cinemas! A name – yours, mine – can be bounded, but an image knows no such bounds: we can read into Joseph Carlson’s work both a fascination for the people who bear these names, and perhaps also a private uneasiness about their prodigious appetite for power.

Because what prevails here is power, imperious and sometimes alarming: let us look at the energy emanating from the signature of Petro Poroshenko, the firmness of Xi Jinping’s or the gleam of Viktor Orbán’s. There is no deviating from symbols such as these. We don’t need a graphologist to read and decipher the mysteries of these signatures. With Joseph Carlson there are no mysteries; the whole story can be read in the images he presents. With good reason: without the text they are to endorse, the bill they are to pass, these signatures are validating nothing, confirming nothing;

they are self-sufficient, as they – like all symbols of power – are mere affirmations of themselves.

But who signs a work of art? Who signs their images, their photographs, other than the artist who created them? The signature of Joseph Carlson is at first nowhere to be seen. Is this a retreat on the part of the artist, far away from the sphere of the political? Rather it is a staging, an exhibition of history, our history, which in our absence and that of our signatures also dispenses with the signature of the artist. Joseph Carlson seems to be telling us that these great names are the names of people who lead us and whom in most cases we have elected. Their greatness is writ large in these letters, in more than just their size. The artist deprives these signatures of their usual frame, infuses them with colour just as Andy Warhol coloured his portraits of heads of state; he sets them in motion and plays with them. He thus calls to mind the freedoms of those who create in comparison with those who rule. An artist’s signature is omnipresent in their works. There is no need for them to expressly add it to what they have created: a wonderful lesson, particularly as the autograph of Joseph Carlson is not exactly eye catching. It appears discreetly on the outer side of the stretcher.

Head Lines. We see outlines, but no portraits. Might our world no longer have a face? If its portrait were taken, would it look like this? Joseph Carlson’s gallery of signatures fills the space once occupied by the portrait gallery. But of what once stood above all else, the faces of the greats, there is now not a trace, as if the inordinate space they take up in the media relieves the artist of the need to depict them yet again. Every individual expresses the present in their own way: in the form of images – an excess of images – or through the absence of images, the absence of heads. And instead through the symbol of their existence. A symbol which endures in a way that only symbols can.

Pascal Dethurens

Signs of the Times

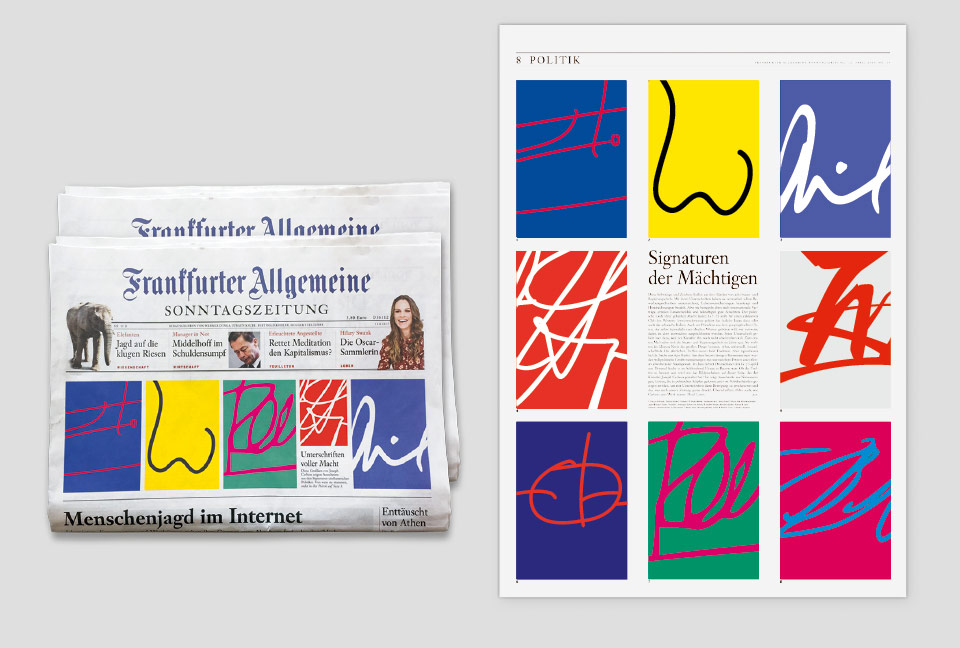

Joseph Carlson’s group of works Head Lines began in 2015 with a white surface traced with a broad, abstract, gestural line in red. The variations in the thickness of the line give the impression that it was painted with a brush. At first glance, an image like this may be associated with the art movements that characterised post-war modernism, such as French art informel or American abstract expressionism — painting trends that documenta founder Arnold Bode proclaimed in the late 1950s to be “abstraction as a world language” and that were widely celebrated as the “signature style” of the Western world.

However, a second look makes it clear that Carlson’s image #1–21.9 — like every subsequent work in the still ongoing series — is a reproduction, created using the technique of Giclée printing.

The surfaces of the canvases are entirely smooth and textureless. They appear as flat as the abstract expressionist motifs in the series Brushstrokes, which the American pop artist Roy Lichtenstein created in the mid-1960s by enlarging and reproducing motifs taken from a comic book. Carlson’s Head Lines too take up hand-drawn lines — more precisely, details of handwritten signatures. Every work in his series crops its gestural motif along at least one of the four edges of the image. The artist reveals who authored each of the signatures appropriated by him. The first image in the series shows a detail of the signature of Shinzō Abe, Prime Minister of Japan since 2012; the second, a detail of German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s signature, an almost comic book-style black flourish against a yellow background; the third, part of the signature of current US President Donald Trump, red hatching along the top of the image contrasting with the dark blue background. If Carlson’s conceptual Head Lines must be assigned to a genre of image, they can be located within the tradition of portraits of rulers and heads of state. This type of image is in fact as old as European portrait painting itself, as noted by the art historian Martin Warnke: “Even the earliest surviving independent portraits,” (those of Rudolf IV, Duke of Austria, and the French King John the Good, both done around 1360), “are portraits of rulers.”(1) Here, however, it should be noted that the Head Lines portraits were not commissioned but were created by the artist of his own accord. In this context, Carlson’s choice of format for the entire cycle — 120 × 80 × 4.5 cm, approximately half as large as a life-size

portrait — can be understood as an expression of distance from the subjects portrayed; Carlson is not laying the foundations for a monumentalisation of these political figures.

While the first three images in the cycle each display a clear relationship between their colour scheme and the colours of the national flag in question, this pattern is broken in the fourth image. The red lines of the signature of Kim Jong-un, the “Supreme Leader” of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, better known as North Korea, stand against a dark grey background. This and subsequent deviations make it clear that Joseph Carlson’s cycle of images leaves plenty of room for subjectivity on the part of the artist, even if he always works with found material. This applies first of all to the decision of which political figure to include in the series at a particular point in time. New inclusions are always inspired by specific events and current developments with a connection to decisions made by well-known and powerful politicians. Only after this does the search for a copy of the signature begin.(2) Which detail of a signature is chosen, and where it is placed on the canvas, is also the result of a very conscious artistic decision. The fragments of writing prompt speculation on the character of the signatory, regardless of the fact that graphology lacks a serious scientific basis. Similarities with the peace symbol, for example, can be seen just as clearly as hints of barbed wire. And the choice of colour too — whether it mirrors the national colours or breaks away from them to a greater or lesser extent — prompts the audience to wonder, as with every portrait, how the artist sees the subjects he has portrayed.

The Head Lines portraits, characteristic examples of conceptual art, first gained recognition via a mass medium and in the context of a major political event whose participants regularly make headlines. On 12 April 2015, the Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung published eight signatures–turned–artworks by Carlson. The signatures belonged to the seven heads of state then governing Germany, France, Italy, Japan, Canada, the USA and the UK, who were preparing for the G7 summit to be held a few weeks later in Schloss Elmau in Bavaria. The series also included the signature of the Russian president, who was excluded from the summit following the annexation of Crimea. Russia had belonged to the G8 from 1998 until 25 March 2014. The annual meetings of the Group have brought together the most important developed nations in the Western world — and, interestingly, Japan — in a variety of formats since the mid-1970s, offering an opportunity to discuss global issues within a small group in an informal setting. Joseph Carlson’s Head Lines thus prompt viewers to reflect on both the reach and the limitations of the political power of rulers. What has actually become of the plans they signed — for environmental policy and the energy transition, for the lifting of trade barriers, for the prevention of epidemics? What diverse economic, political and technological forms of power stand in opposition to the power of the signatories? What role is played, for example, by the proverbial “power of the factual”?

The Head Lines portraits depict power not least as something abstract — the signatures are illegible; and as always partial — the signatures are never complete, only individual details are reproduced. Carlson’s Head Lines can thus also be understood as signs of the times, times wracked by a whole host of crises and challenges. These include not least the crises of legitimacy affecting political and economic power. Carlson works with signatures of democratically elected heads of state and government, but equally with those of autocrats. This also serves as a reminder that the line between democratically legitimate forms of government and autocratic ones can become thoroughly blurred. Last but not least, we must turn our attention away from the political scene, communicated via the mass media, which Carlson’s Head Lines make reference to, and back to their conception.

An analogy can be drawn here to a project by the French literary scholar and philosopher Roland Barthes. His work on Japan, published in 1970 under the title “L’Empire des signes”, was not an attempt to create an objective image or ideal image of the country, but rather a description of it in terms of “what Japan awoke in him”.(3) “I can,” said Barthes, “— though in no way claiming to represent or to analyse reality itself (these being the major gestures of Western discourse) — isolate somewhere in the world (faraway) a certain number of features (a term employed in linguistics), and out of these features deliberately form a system.” Similarly, Carlson’s method of choosing details of signatures and constellations of colours gives an impression of what a political event or a decision-maker “awoke in him”. The Head Lines portraits take “a certain number of features (a term employed in linguistics)” and use them to form a system whose potential interpretations remain just as much in flux as political developments themselves.

Barbara Hess

(1) See Martin Warnke, „Herrscherbildnis“ [Portraits of Rulers], in: Handbuch der politischen Ikonographie [Handbook of Political Iconography]. Vol. 1: Abdankung bis Huldigung [Abdication to Homage], Uwe Fleckner, Martin Warnke and Hendrik Ziegler (eds.), 2nd, revised edition, Munich: C. H. Beck 2011, p. 481–490.

(2) Joseph Carlson to the author, 24 May 2018.

(3) Roland Barthes, Empire of Signs, translated from the French by Richard Howard, New York: Hill and Wang Noonday Press 1989, p. 3.

Expressionist Gestures of Power

Since Donald Trump took up residence in the White House, the signature as a symbol of power has been more present than ever. This President has turned the signing of laws and decrees into a thoroughly staged affair, gathering members of the government around his desk alongside ordinary citizens involved with the issue at hand, signing the document as they all look on and then brandishing it before the cameras. In this way, he attests his signature once again through a gesture of demonstrative acknowledgement. His signature has become perhaps the most famous in the world. The signatures of most other leading politicians, in contrast, are hardly ever made public, and those of powerful figures in the economy and other fields even less so. Particularly as a public ceremony is in any case only common practice for the signing of especially important, international agreements.

But the fact that even Trump, of all people — who generally cares little for conventions and political traditions — so diligently celebrates the signing of legal documents also shows how deeply rooted the idea of signing is in cultural history. It is not at all restricted to Western cultures; historically, everywhere that something was set in writing, it seemed necessary to have a way of expressly reaffirming what was written, of confirming its validity or indicating the authors or people responsible. An attestation is needed as a binding indication of the nature of what is written for third parties. In itself, written text is too open to interpretation, too easy to detach from the original intention behind it. Special stamps were often used in the past to authenticate written documents, as were unique symbols or fingerprints. These days, signatures have become the global norm — something of a paradox, as it means that writing is safeguarded simply by more writing.

This paradox is supposed to be resolved by making signatures as distinct as possible from other writing. Ideally, a signature makes both the gesture of attesting and the declaration of the signatory’s intent expressly visible. This often gives signatures a particularly dynamic effect: the more quickly and energetically they are written, the more powerfully they can manifest the signed text’s claim to validity. And when the representation of the individual letters is unusual — ideally, unique — the reader has the impression that they can discern the personality of the signatory in all of their individuality, in their specific will. Signatures, thus, were expressive long before expressionism came to be — and they still are today.

This double wilfulness of signatures forms the subject matter of Joseph Carlson’s images. In a series of steps, he brings out this wilfulness — this expressionism — yet more clearly. By isolating and, in addition, heavily magnifying the signatures of presidents and heads of government, he turns the written lines into powerful entities in their own right. In this way, the gestural habitus is elevated to a performative act. By only depicting a part of each signature in his images, forcing it beyond the bounds of the canvas, he makes the effect all the more energetic — indeed, downright explosive.

They occupy the entire space, but at the same time become illegible and thus become an occurrence of striking and always intensely individual lines. By then using a single block of background colour to create a contrast with the colour of the signature, he intensifies the luminous power associated with signatures and thus also highlights all the more clearly the claim to validity that they represent.

While Carlson’s images turn the idea of signing into something visible and tangible, they do not, strictly speaking, show signatures at all. Nothing is being signed here. Removed from all context, these signatures are at most attesting themselves — and are thus intensified yet further. They become the subject matter itself, rather than an addition to it. This is the origin of the title Head Lines, which in German plays on the parallel between the words “signature” (Unterschrift, “under-writing”) and “headline” (Überschrift, “over-writing”). Here, it becomes clear once again how much of an impact a signature has, how much it is, in fact, the crux of the matter.

Alienating by disassociating, and thus shifting the gaze to foster new insights, is a long-established practice in the visual arts. It would be a delight to see Carlson’s cycle exhibited alongside a series of photographs produced in 2015 by Taryn Simon. Under the title “Paperwork and the Will of Capital”, she photographed bouquets of flowers modelled on the floral arrangements which decorated the venues where important agreements were signed. Just as Carlson focuses everything on the signatures, Simon reduces each event to the floral decorations which accompanied it. She researched the background to the signing of each agreement as well as the exact composition of the floral arrangements, even drawing on the help of a botanist. She only actually photographed “impossible bouquets” — arrangements made up of flowers which could never naturally bloom at the same time in the same place.

Where Simon foregrounds the incidental, the purely decorative aspect of an enactment of power, Carlson extracts the element that gives this power new force on each occasion. And while Simon’s work is a stylised presentation of deals and agreements as aesthetic, artificial events, in which the impossible bouquets must also be read as a gesture of power — as a victory over nature — Carlson manages to make visible the ambivalence inherent in an act of exercising power. In his images, the signatures appear eerie and aggressive due, precisely, to their luminosity; but they are also, in the abstraction of writing into lines, simply beautiful.

Wolfgang Ullrich

Abstractions of Power

How do people sign their names? What does that say about them, about their personality? A whole scientific field — graphology — is based on these questions. In industry, recruiters consult expert graphologists when assessing candidates for executive roles. In politics, the general public can have its say whenever politicians’ signatures appear for all the world to see on treaties, trade agreements or other important national documents.

We draw our own conclusions — for example, from the jagged signature of Donald Trump. The narrow letters with their sharp vertical spikes are brandished to the cameras by the President, his face set in grim determination, each time that he signs another decree manifesting his desire for change. The signature has been compared to a frequency graph of the screaming of demons, and to an ECG display of someone having heart palpitations. Analogies with the nature of the signatory are popular. When the new German government finally signed a coalition agreement after months of negotiations, the signatures of the party leaders were promptly subjected to the same public scrutiny.

Both the personal aura and the powerful act, both the fleeting nature of the rapidly scrawled lines and the permanence signalled by a politician’s signature on an official agreement — all of this also plays into Joseph Carlson’s work. But in his images, he shifts the signatures away from their axis. His Head Lines show only details of the looping or staccato penmanship of international heads of state. Sometimes Carlson moves them to the right, sometimes to the left; sometimes higher up, sometimes lower down. Following this displacement, the artist magnifies the signatures to giant proportions and uses intense colours to set them off against their background.

Joseph Carlson is an inspired graphic designer — that much is clear at a glance. It is not immediately clear who is the author of all of these decorative loops and scrawls. The thrill of the Head Lines arises from the knowledge that they conceal the British Prime Minister, the President of the USA or the Austrian Chancellor. Some signatures — that of the Turkish President, for example, or the Greek Prime Minister — even seem to have been rotated, so wild are the lines on the canvas.

Which letter from Angela Merkel’s signature is shown in Carlson’s image? This undulating flourish can hardly be an A. And has Raúl Castro, the Cuban President, written the first letter of his first name in reverse? Carlson’s images may well symbolise the cumulative potential of political power. But they are essentially just signs, which can also be read as abstract paintings.

The history of the signature stretches back to the 15th century, when the globalisation of trade first began and merchants had to sign agreements with one another over vast distances. Rulers had been sealing their pacts with one another in writing long before this. The signature has always been a sign of approval, of agreement. This is the source of the German word for signature, Unterschrift, literally “under-writing” — meaning that the signatory has read the full text and added their name below it only after reading.

A handwritten name at the end of a contract still has the same legal power today, even centuries later. It authenticates a multilateral agreement. Even in the age of electronic media, this hasn’t changed. This is why the moment of concluding an agreement — especially between states, sealed by the handwritten signatures of politicians — still has the same significance. But Joseph Carlson also extracts aesthetic added value from the politicians’ signatures and shifts them into the sphere of the artistic.

We could identify this as a form of glorification. Or we could observe that, here, the “art of government” discovers itself.

Nicola Kuhn

The Power of Art

Joseph Carlson has been developing his artistic approach for a number of years in the form of consecutive series of photographs, of paintings, of sculptures and of structures in three dimensions, and of works using found objects, surfaces and various fragments, adopted and revealed by his sensitive, creative processes.

His new series Head Lines continues this line of research. Carlson collects the signatures of a range of heads of state and chooses a detail of each one to magnify and isolate and then place on a monochrome surface. It is commonly accepted, in line with the dictionary definition, that a signature is the name of a person authenticating a contract or a commitment. In art, the signature of the artist authenticates their work. Inscribed on the surface of the work it is verifying, the signature is a unique autograph. Usually legible, it can be either highly ornamental or reduced to initials. Paradoxically, it is anonymous when it shows the stonecutter’s mark. It even precedes the invention of writing, again anonymously, in the form of ancient handprints on the walls of Neolithic caves.

The series Head Lines by Joseph Carlson is based on the signatures of the great and powerful, autographs which he adopts and integrates into an artistic project where the subject – the signature fragmented, dissected, decontextualised – becomes the object of a pictorial representation. The signature on an artwork, as we have said, almost always reproduces the name of its author perfectly legibly. Conversely, and with very few exceptions, the signature added to the bottom of a written document is perfectly illegible. A sort of graphic “ready made”, the signature changes status, dimension and nature. A single, partial element of the signature will be retained, magnified, stretched, coloured, transformed. The autograph of Donald Trump, Angela Merkel or Emmanuel Macron, already difficult to identify in its initial form, will reveal nothing more than a collection of lines, a clean and dynamic outline whose shape, colour and graphic precision will define a new space drawn on the monochrome surface of the work. The line and the colours (those of the surface and those of the strokes that cross it) constitute the two core elements of an apparently abstract pictorial composition. However, the “neutrality” of the background, no matter the colour used, allows the line to enclose and delimit a space. From a formal point of view, the Head Lines images are an essentially harmonious assemblage which could be qualified as a gestural abstraction, devoid of lyricism, and measured by the rigorous flexibility of the lines associated with a geometrically abstract shape, determined by the absolute immutability of the monochrome colour scheme.

A signature resolves itself into a work of calligraphy produced by a rapid gesture which is spontaneous yet controlled. The way that Joseph Carlson uses the signature distances it from this emotional spontaneity, highlighting a rigorous outline which establishes a relationship between the line and the background and affirms the remarkable equilibrium of the relationship arising from the movement of the coloured line and the surface on which it is traced. At its core, this is an interpretation of a unique sign belonging to nobody except its author, a deeply personal sign which identifies the signatory alone.

Each work can thus be seen as a portrait, a paradoxically abstract figure where the sign transformed by the artist’s will delivers an “image” representative of the person who is identified by it. This makes it clear that the Head Lines images do not merely express a manifesto where the artistic aspect is reduced to its simplest expression. Because the transgressive use of the signature also very much consists in its artification (to use the term adopted by sociologists), that is the transformation of non-art – a signature – into art. A graphic sign which is meaningful but not artistic is thus recharacterised by the artist’s will. It is through this decision that Joseph Carlson gives his series its undeniably political dimension. While the mark of authentication added to the bottom of a document gives it an essential inviolability, the way it is wilfully appropriated by Carlson calls into question its value and at the same time reveals a more intimate image of its author. It is well known that, throughout world history, treaties which were duly signed and countersigned have been disregarded, defaced, violated, even annulled through nothing more than the will of a leader contesting the validity of a commitment.

The Head Lines series, a pell-mell collection of reminders in the form of the cropped signatures of figures such as Shinzo Abe, Kim Jong-un and Barack Obama, thus equally exposes the fragility and impermanence of every official document, regardless of its significance, whether political, economic, ecological or cultural. Recent events in the world of international politics have already confirmed this fragile volatility. The theatrical manner in which the current President of the United States exhibits his signature is much more than just the validation of the act; it is an affirmation of his person. By placing it along the upper edge of the image, Joseph Carlson reproduces only the lower part of the signature – is he calling into question its legitimacy? At the bottom of another work, the vivid, diagonally drawn fragment of Kim Jong-un’s signature appears as a symmetrical yet contradictory response to that of his rival and highly improbable new partner. Does Angela Merkel’s “portrait”, reduced to a loop resembling an inverted question mark, reveal a particularly topical aspect of the German Chancellor’s political situation? Each autograph selected by the artist illuminates a reflection of the personality and doubtless the life experiences of the signatory, expressed not simply as a graphological interpretation but also via the choice of layout and colour and, of course, the element of the signature used and the way the artist has chosen to place it on the canvas and thus call it into question. Because it is very much the reliability, the credibility of the figures who exercise power today and have exercised it throughout history which is the subject of Joseph Carlson’s pertinent series.

However, the critical gaze of an artist in no way undermines the artistic dimension of the project. The works in the series Head Lines display expressivity and quality of composition alongside their political aim and their criticism of world governance. This aesthetic dimension of the work, far from concealing the political element, elevates it.Writing as a constituent element of paintings, aside from the artist’s signature, abounds in 20th-century works from Picasso to Picabia, Duchamp to Magritte, and in the conceptual art of Marcel Broodthaers, Ed Ruscha and many others. But Joseph Carlson includes writing while excluding the possibility of reading, of decryption in the literal sense. The written signature, above and beyond – or, more precisely, due to – its formal artistic value, is a graphic translation of a kind of symbolic representation of power, all the more evident as it is reduced to a fragmentary transposition.

Each element of Head Lines displays skilful composition and a remarkable mastery of colour harmony. The revisited lines of the signatures are adroitly coordinated with the backgrounds, whose monochrome perfection resonates with the vibrant colours of the lines, curves, dots and symbols selected. And yet the message is not diluted in any way by the aesthetic value of the work, a value which it conveys unambiguously as the artist leads the audience to discover the pages of a narrative firmly anchored in the modern age. Uncompromisingly contemporary, Joseph Carlson’s art nonetheless has an undeniable formal appeal linked to its flawless execution. The rigorous composition, the masterful harmony of the colours and the precise distribution of space confirm beyond a shadow of a doubt that this is the work of a painter. It is precisely this faithful adherence to the criteria for the execution of a painting that, through the combination of the political aim with artistic expression, lends such impact to the work of an artist whose political commitment is unquestionable. A commitment to engage with power and its representation, in a world where the omnipresent and invasive image of the figures who hold power most often masks the reality of their position and the true foundation of their political message. By demystifying the power of their signatures, he relativises that of the authors. Joseph Carlson’s work is not a militant manifesto reducing this commitment to aesthetic artifice. It is precisely the affirmation of the project’s aesthetic value which ensures its effect.

With an approach that is never anything less than creative and inspired, Joseph Carlson invites us to share his critical view of the modern age, where art and the power of art remain indispensable as they reveal – doubtless better than discourse – the reality of the world.

Jean-Yves Bainier